… Is acid in my belly at the very best”

I haven’t blogged in a long time. Mainly because I wonder about the general futility of words in the ether; or the ego driven farce that leads one to believe one’s words mean anything to anyone other than those that tolerate them in late night ramblings in a bar (or more recently on zoom); but equally because there’s just been too much going on.

As I write this Morrissey is telling of how he’s, “not sorry for all the things he’s said. There’s a wild man in [his] head.” Reflecting on some of what I’ve said I wonder if I should be sorry. I am at a point where transition has been going on for so long it’s hard to call it that any more – either transition or a point. Or a transition with little sense of point at times?

What I do know is I’m no longer who I was. In some of the resources that I wrote for the work I began some years ago under a MAT, and now use with children that have similar needs and challenges but in a very different circumstance, I have a slide that takes it title from a line spoken by a boy who had been on the verge of permanent exclusion. “You don’t want to be who you were,” he says.

I hope he is still a little bit of who he was. He’s a really likeable lad with a cracking smile, sense of purpose and curiosity in his eyes that I’m sure would make him an amazing learner. Hopefully that’s still there but now accompanied by a sense of purpose and ability to navigate the world and with a language for negotiation and self regulation that may have been missing in the past. I too, “used to be a sweet boy,” and I’m not sure what went wrong (sorry, more Moz – he’s hard to shift) but I have some ideas.

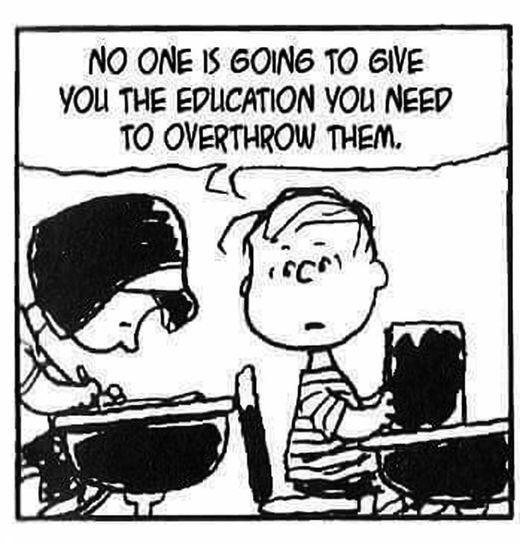

Nikole Hannah Jones is a Pulitzer prize winning journalist who, in conversation with Carlos Moreno of Big Picture Learning, said that we have it wrong when we try to fix the system. The system, she says, isn’t broken – it’s doing what it was designed to do. She was referring to education in the United States but the same was said only a short time later with regards to the police system there and the systemic racism that has us hearing far too many names like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and wondering who will be next and how long it will be before these names stop coming. A question asked by Marvin Gaye in ‘What’s Going On?’ and before him Billie Holiday singing of, ‘Strange Fruit.’

So what went wrong for this sweet boy? Why doesn’t he want to be who he was? And how arrogant is he now throwing in references to atrocities and trying to align himself with those that have lost their lives? Well, crucially I don’t align myself with the victims in this or even the campaigners (no matter how much I would like to and try to) but more with the systems that maintain the inequalities and the status quo – the system that isn’t broken but I’ve kidded myself we can fix from within. I told myself this over and over when working for a multi academy trust in a disadvantaged area. That enabled me to build a school in my home town and really do something different for the families and the community there. Friends questioned how I could go to work in an organisation that seemed to embody the system around us and was at odds with what I believed in. I did it, because all the while I genuinely thought that changing from the inside rather than shouting from the outside was going to have a bigger impact.

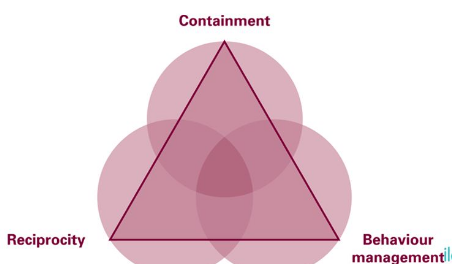

I think I did make some changes. I was the architect of the first internal alternative provision in the trust, one that is now referred to by a wide number of influential people as a model for keeping learners within the family of a trust rather than pushing them out and ultimately I’m proud of what I established. But when I decided it was time to move on it really was the most mutual of decisions. Our relationship had come to an end and, while we both got something from it while it lasted, it was over and wouldn’t have been any good for either party to drag it on.

What I began to recognise there, even subconsciously, was what Nikole Hannah Jones brought into sharp focus for me more recently. That even by trying to fix a system from within you can be perpetuating a system that really needs wholescale change. Even more recently than the interview with Carlos I was listening to a podcast by the Irish artist and musician (and I think philosopher in waiting) Blindboy where he interviewed the writer Emma Dabiri. She spoke about how it was the Irish that were involved in one of the first examples of race being used to divide people.

In Barbados in the 1700s indentured Irish and black slaves came together to challenge the authority of the landowners and caused some real panic among the gentry. The plantation owners needed a way to break down this union and regain control and struck upon the racial differences between the two groups as a way of doing this. Readily painting the black slaves as ‘the other’ they were able to make promises to the white Irish of jam tomorrow as they were white and had rights, a voice, and the potential to have what the landowners had if only they played along and abandoned their loyalties to this group who didn’t even deserve to be heard, being as they were, lesser in every way. The indentured Irish (in a manner they repeated in New York later by distancing themselves from the negative perceptions of being Irish and joining up as ‘officers’ as opposed to ‘overseers’ for the slave owners) went for it. The desire to raise up the ranks and not be on the bottom rung led them to readily turn away from their comrades and allies. Dabiri says it is this move through allegiance and comradeship to coalition that we now need to build if we are to move things on from cancelling shows, hashtags and taking knees at football matches.

Dabiri used the analogy of the slave ship to great effect and it is an image that has stuck with me since first hearing her on the podcast. White Europeans would, she said, do all they can to get as far away from the slaves down in the hold as they could. Charting their success and progress to the upper decks of the ship, to please and appease the owners of the boat while – I imagine – a number told themselves they were doing good things and seeking to change the running of the boat. But they were still on a slave ship.

During the same, and subsequent podcasts, the host has shared his internal wrestling with social media and in particular twitter. Rather like the teacher wondering about the self indulgent nature of these musings he does question whether it’s an ego trip to do such wrangling but (unlike the aforementioned educator) he has 250,000 people following his posts so sees that he has some sense of duty to do right by them. In doing so he explores the nature of the platform and how the algorithms are arranged. Having consciously taken a step back from Twitter lately, or at least tried to use my account to raise up the positives I see in others as opposed to getting into the tit for tat that coloured my use previously, it’s to see exactly what he refers to. That the platform feeds on, and needs for its existence, arguments, oneupmanship, cruelty and attack. It creates conflict because that is the business model. There is no grey, only black and white. No nuance only binary. No little bit of both, just either or. No room for truth but only my truth versus yours.

This is why the same debates roll around; mobile phones; exclusions; progressives or traditionalists; uniform. This is why those that are able to encapsulate their position in a pithy, edgy and cutting soundbite will rise to the top. This is why the whole environment becomes so tribal, divided and divisive. Because it’s a game. The system isn’t broken, it’s doing what it’s designed to do, and even those that feel they are winning the game are merely pawns being played by those that profit from the game. It’s designed to do this, to push people to polarity as a way of progressing and everyone gets drawn in because our egos like it when we get likes.

So maybe it’s time to step back. If not from use then from the conflict. Find other voices to build with and other ways to do it. To resist the urge to respond to the negativity and look instead to the positive. Even the act of standing up for another has become monetised and part of the game as the to and fro builds. Find our allegiances through supporting the good work of others and leave the detractors be. The voices you wish to challenge get louder when you do because that’s what it is designed to do. It’s designed to drag you in and wait for the shouting to escalate. If you’re getting likes from pointing out a flaw in someone else then you aren’t riding the waves, you’re in the blender. So don’t do it.

And this isn’t about Twitter. If the slave ship is an analogy, then twitter is a microcosm. If you champion something there, or challenge something there because you’re seeking approval, acceptance or to convince others of an opinion then ask why. Why do I care? This environment thrives on discord and conflict and serves only to perpetuate the status quo. By seeking affirmation here am I building a new system or seeking a higher deck? How does this carry across to what I do in other areas of my professional life? Am I seeking contracts and favour from the same people as those I come into conflict with? Is my disagreement with them because I need to carve a clearer path to favour with those in power than they have? Or do I really want something different? If I do then I need to think differently, speak differently, act differently. I need to find allies and comradeship to build a coalition based on collegiality rather than just overcoming those that I am in conflict with just to seek favour with the same audience. Am I building a new ship or an indentured Irishman courting favour?

If we subscribe to this mindset, encouraged by a platform that brings out the very worst in us but not just confined to those 140 characters, then what will die is any real, considered and collegiate voice. Any sense of allegiance or growth. Anything that will lead us to overcome those in the seat of authority. Anything that will allow us to build a new system rather than perpetuate the old. As we eat each other to stay alive and seek a higher deck on the slave ship.

Go well